Let’s talk a bit about the angle of the wall.

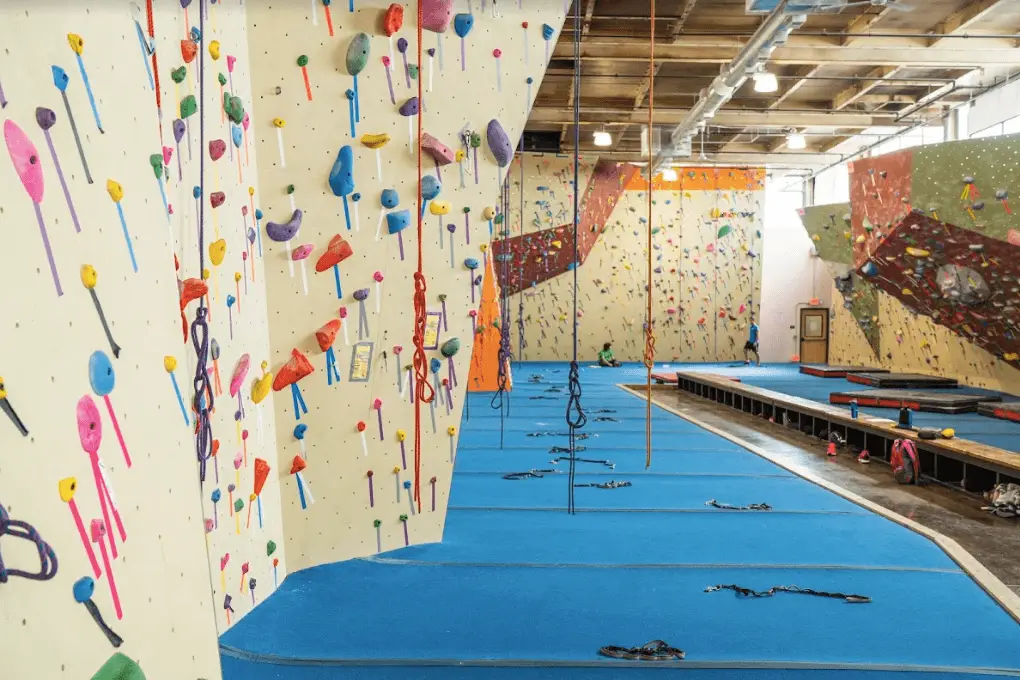

Climbing, like many sports, is full of its jargon. What’s slab? What does it mean to top-rope? (For a comprehensive, though not exhaustive list, see our glossary). In this article, we’ll learn all about indoor climbing walls and their angles.

When discussing “how steep” a wall is, for instance, we have three general terms: slab, vertical, and overhang.

Vertical

Overhang

Slab

Unfortunately, while these terms sound precise, they are used slightly differently by different climbers. In turn, their meanings become a bit fuzzy when used in general conversation.

That fuzziness often leads to misunderstandings between climbers and instructors. So, in this article, we will use a more concrete set of definitions. And we apologize in advance to any experienced climbers who may take issue with us redefining a beloved term!

Understanding the Impact of Gravity and Angles

Our criteria for these definitions revolve around gravity. To be more precise, it revolves around the different “feel” that gravity imparts to move on different terrain.

The feel of doing a move on slab is generally different from doing the same move on a vertical or overhanging wall (and vice versa). This is true even though the mechanics of the move may be identical.

While the idea of feel may sound more subjective than we would like (and, in some ways, it is), in this case, it is nonetheless quite useful. Gravity pulls on all of us the same way. It, therefore, has a predictable impact on how climbers apply their skills to different wall angles.

Vertical Climbing Wall

Vertical walls are the easiest to define–a vertical wall is essentially perpendicular to the ground.

For example, look at the wall in your house, office, or coffee shop (wherever you may be reading this). That is a vertical wall (unless the builder made a serious mistake).

Bolt some holds to it and you have a vertical climbing wall!

Though this definition is very precise, it is, however, a bit misleading. Other than in indoor climbing gyms, it is extremely rare to find rock climbs that are perfectly vertical for a meaningful distance.

There are always minor variations in the real world. Consequently, it is nearly impossible for a human to feel the difference between a wall that is exactly vertical and one that is, say, 2 degrees overhanging, or 3 degrees less than vertical.

For our purposes then, we will call a vertical climbing wall, anything that is between a few degrees less than and a few degrees more than vertical. For the jargon hunters among you, most climbers would refer to this as face climbing.

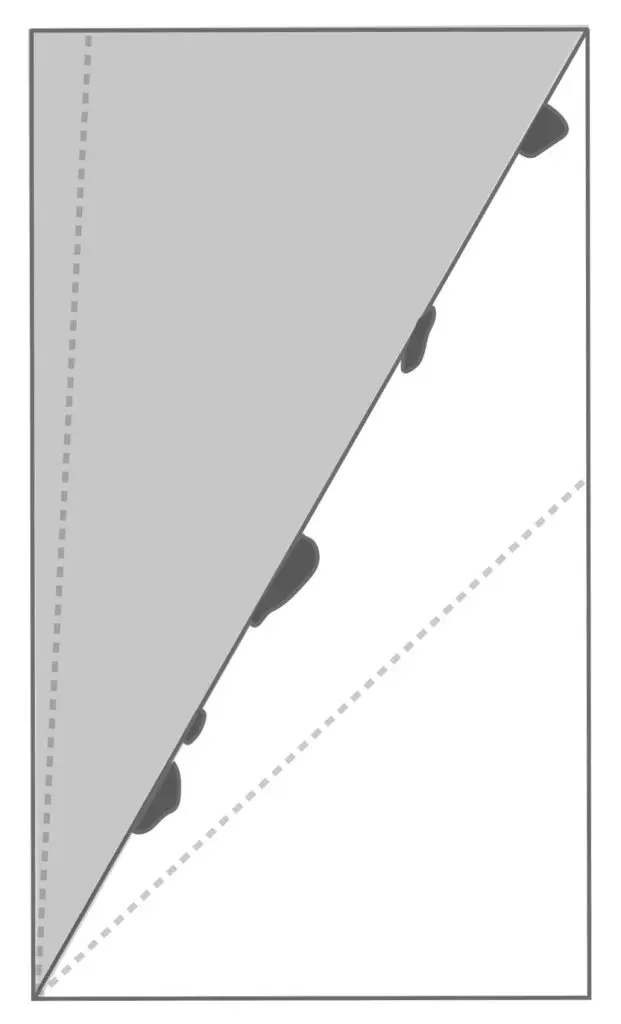

Overhang Climbing Wall

With this idea of vertical under our belts, we can now easily define an overhang as any climbing surface more than a few degrees steeper than a vertical wall.

In practice (especially in indoor climbing) most climbers would argue that an overhang is any wall that is 5 or 10 degrees past the vertical or steeper. The most extreme overhang would be parallel to the ground.

For instance, look up at the ceiling. Imagine bolting some holds to it and trying to climb. Now that is an overhang! Luckily, most overhanging climbing is nowhere near that steep, and for the basics section of this book, we will be looking at angles in the 10 to 30-degree range.

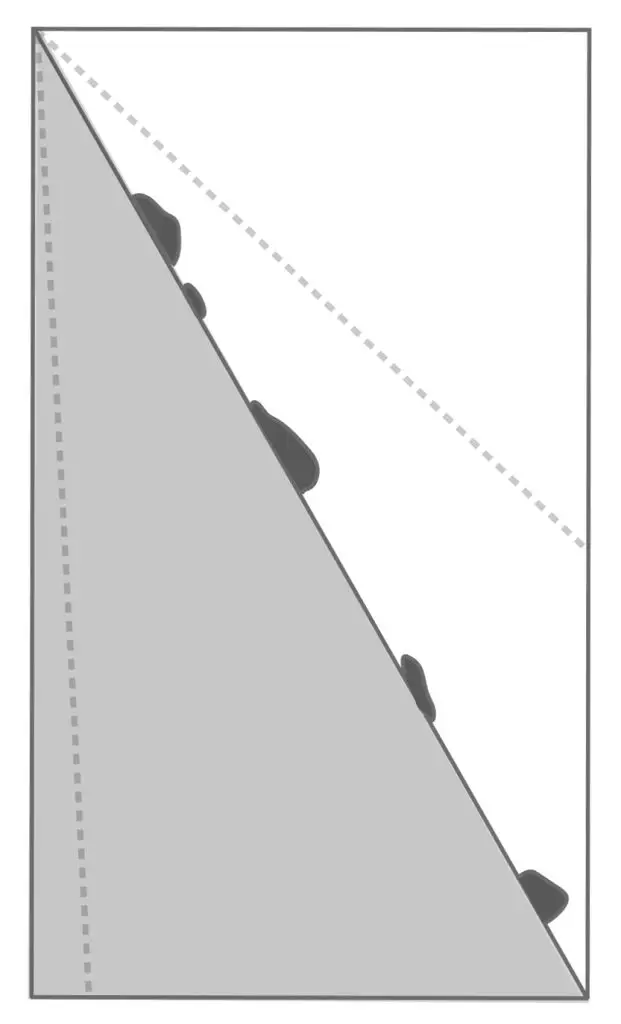

Slab Climbing Wall

Finally, we come to slab climbing, which, if you haven’t already guessed, would be any wall surface that is a few degrees less than vertical or more.

In practice, of course, there is a limit to how low an angle you can get before you are no longer climbing a slab, but rather walking up it. In the real world, slabs tend to bottom out, so to speak, at about 20 degrees less than vertical, though there isn’t a hard and fast ruling on that.

Slab climbing has a special place in learning to climb, so much so that many climbers frequently refer to it as technical climbing.

The nature of slab is such that it is the only angle on which a climber can reliably put 100% of their weight on their foot, and let go without falling.

While there are special circumstances where we can let go with our hands and remain on the wall at steeper angles, these options are rare and require advanced skills. On a slab, on the other hand, a skilled climber, armed only with the basics, can, in theory, let go at almost any point and carry their entire body weight on their feet.

The Importance of Training on Slab For Other Climbing Walls

Why is training on slab important? Slab is the only surface where we can be nearly 100% efficient in our climbing. (See our article “How to Climb Efficiently.”)

In addition, the lower angle of a slab naturally reduces the load on our arms. Therefore, it makes learning and practicing new skills much easier, since we generally fall due to technical mistakes, as opposed to merely tiring out.

As such, slab is the best place to not only learn basic skills but to refine them to a greater level of expertise.

In fact, as a general rule of thumb, as climbs get steeper, the load on our arms becomes greater. The important thing to keep in mind is that nearly all climbing skills can (and should) be learned on slab first. Remember that the mechanics of these skills are identical on all angles, even though they tend to feel different as the angle changes.

All About Indoor Climbing Walls

In the climbing world, there are vertical walls, overhang walls, and slab walls. Gravity affects the feel of climbing even though the mechanics may still be the same. Vertical climbing is perpendicular within a few degrees and an overhang is much steeper. Lastly, slab has a negative degree and is crucial in learning how to climb efficiently. Don’t forget to practice on slab to master the basics of climbing!

All material is reprinted with the permission of the author. Copyright 2022 David H. Rowland. All rights reserved.